Why Do I Run?

A Journey Through Evolution, Trauma, and the Neurobiology of Change

TL;DR: I run to make myself as adaptable as possible, to challenge my own ignorance, to process trauma, to reassert my agency in relation to suffering, to teach my nervous system that I’m safe, to change how I feel on demand, and to find new vantage points from which to examine my life and the world around me.

I blend science, lived experience, and radical honesty to show how trauma, addiction, and resilience are wired into the brain — and how we can rewire them for lasting change, building toward a community that unites research, training, and recovery. Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Introduction

Why do I run? Amid a string of flight delays in early August 2025, this question struck me. In younger years adrift in the Denver airport, perhaps I would’ve been thinking about the mysteries that lay there rather than something so seemingly mundane. People run because it is good for them and it makes them feel good, right? Simple enough?

I started running voluntarily at 17. I ran before that, sure, but I didn’t do it on my own volition really. When I started running voluntarily, it always made sense to me — a swirl of thoughts on a merry-go-round that coalesced into a simple internal truth, I need to run.

Back then, in hindsight, I was running to escape a chaotic home environment, untreated ADHD, and depressive and anxious tendencies I didn’t yet realize were abnormal — let alone know how to handle. I couldn’t fix others, and I was only just beginning to learn the ropes of changing how I felt through substances. But running? That was something that was mine — something I could control. If I wanted to run four miles, that was within my power. No coach, sibling, or parent telling me to do it, or to share it. I could stop or go at any time. It was just mine.

Over the years, my understanding of why I run has only deepened as I’ve learned more about how our bodies work — and how I work.

But even though the answer felt clear in my own head long before I sat down to write this, I realized that putting why I run into words would take far more effort, and more thought, than I expected. Along the way, I also found some new nooks and crannies within my own understanding.

I’ve often noticed that I tend to focus on the what and how of something I want to do. Yet when I focus on the why — like an internal tattoo of sorts — it imprints much better. With such an imprint, I become far more capable of actually doing it, and the act itself takes on deeper meaning. It not only gets done, it matters. Life feels more cohesive, more rich. Find my why, and the results seem to stack in ways that surprise me — like Bellatrix Lestrange’s vault in Harry Potter, where every ornament touched spawns more and more copies, quickly overflowing beyond what was anticipated.

About 3 years ago, after I ran a marathon (my only one thus far, no need to oversell yourself these days, shoutout radical honesty), a coworker asked me, half‑amused, “Do you like torturing yourself?”

And, well, Adam, after about 1100 days of thinking on it, I guess the answer is c o m p l i c a t e d.

The Evolutionary Background

In order to get to why I run, we must first start with some background on running, nice and existentially. Running is ancient. For the sake of this article, we’ll consider running here as an animal’s ability to move rapidly across land using at least two limbs in a rhythmic pattern. I say this because the definition of running was a stranger and more complicated rabbit hole than expected. By this definition, running has existed on Earth for roughly 400 million years.

Humans, on the other hand, have only been around for about 300,000 years. In all likelihood, we’ve barely contributed to the total number of miles run on this planet. Your Hokas can, well, politely fuck off — barefoot running wins by a landslide. Time-wise, by these estimates, we’ve existed for just 0.075% of the time running has been around on Earth (part of me goes, Mitchell, significant figures, you’re better than that).

On the far left of the timeline, there’s a thin red line showing how long humans have existed compared to how long running has. It’s so thin you might not even notice it — blink and you’ll miss our entire species, existential FOMO of a sort.

So:

Why has running stuck around for so long?

How are we adapted for it?

Why does it matter?

Why do I run?

A cascade of questions, one flowing into the next.

Take your marks. Get set. Go!

From the first reptiles sprinting to escape predators, to dinosaurs thundering across floodplains, to mammals darting through prehistoric forests — moving fast on land has been a survival cornerstone.

Two general domains explain why.

Escaping Harm: Running improves the ability to rid yourself of danger: predators, weather, hostile rivals. This may keep you alive long enough to have a shot at reproduction.

Obtaining Resources: Running helps you reach what you need to survive and reproduce faster: food before competitors get there, water before it dries up, shelter before the storm, even mates before adversaries arrive.

Evolutionarily, it’s far easier to build an animal that can quickly change position in two (sometimes three) dimensions than one that can somehow meet every need without moving swiftly when it’s advantageous. To survive without speed, you’d have to be either immune to every external threat — armored against, say, claws, teeth, frostbite, fire, infection, radiation — or stocked with endless internal resources and the ability to regenerate from any external harm.

Plants, for example, make food using sunlight, but they’re rooted, utterly dependent on water and nutrients coming to them. When conditions shift — drought, predators, shade — they can’t escape. Some animals, like turtles, take the armor route instead of speed. They move just fine in water, sure, but plodding on land, and their land strategy only works in niches where hiding inside a shell is enough to survive.

Both options are energetically disastrous. Internal reserves run out, armor is heavy, and hauling an abundance of resources or heavy armor around makes you slower and more vulnerable. There’s also a trade‑off. Energy spent on constant self‑repair or heavy armor is energy you’re not using to compete, hunt, or reproduce. Simply put, being able to run stacks the odds in your favor that you’ll survive and reproduce.

Mobile animals, in comparison, took the other path — speed — solving both sides of the survival equation with one adaptation. Running gets you away from what can kill you and toward what keeps you alive. That dual advantage is why the movers, not the rooted or the armored, dominate the planet’s most competitive ecosystems.

Entire evolutionary arms races have been fought in footspeed — longer limbs, lighter frames, spring-like tendons, better cooling systems, you name it. Each new running species inherits the physical and neurological blueprint of the ones before it, the slow chisel of evolution carving ever more specialized runners.

Is today’s iPhone better than the original? That’s what I’m getting at — but for running. Each generation builds on the last, refining strengths, eliminating flaws, and becoming more seamless in how its components are integrated. Humans are basically the iPhone 100, at minimum, when it comes to running.

Land Speed Demands Forecasting

You might be thinking, Okay, I get it. Makes sense why running has evolved. Get to the point.

So, let’s pass the baton. What does all this mean for us — not just in how we run, but in how running may have shaped our brains?

Running didn’t just sculpt stronger legs, it upgraded the brain. Once animals evolved the ability to run, survival demanded they get better at rapidly and accurately predicting the world ahead — shifting terrain, predators in pursuit, prey zig‑zagging for its life — and adjusting on the fly. Those that couldn’t predict fast enough stumbled, got caught, or missed their chance at food — and were far less likely to survive, let alone reproduce.

But, you might say, life began in the oceans. And you’re right, as best we can tell. For hundreds of millions of years, animals existed only in water, and fish were the first to evolve the ability to forecast motion — to track prey, dodge predators, and navigate currents. (Side not, in writing this, I realized we don’t even have a word for “running” when animals swim fast — a linguistic oversight, in my opinion. Someone, please, do something about this.) Some of these aquatic creatures eventually crawled onto land, adapting their bodies — and eventually their minds — to an entirely different world.

Prediction on land posed a far harsher challenge than in water. In water, the terrain is fluid, continuous, and fairly uniform in friction. A miscalculation slows you down, but rarely stops you cold. On land, one wrong step can send you crashing to the ground. Land is discontinuous — rocks, holes, branches, sudden changes in grip — and gravity is the ever‑present bully waiting to pull you down the moment you falter. Water smooths motion, land punishes it. Acceleration and deceleration are sharper, and every footfall has to be more carefully calculated.

This new environment likely turned an existing skill — prediction while moving rapidly — into something far more sophisticated. Simply put, there is less room for error on land than in water, and so our predictive abilities had to evolve accordingly.

From the Cerebellum to the Cortex

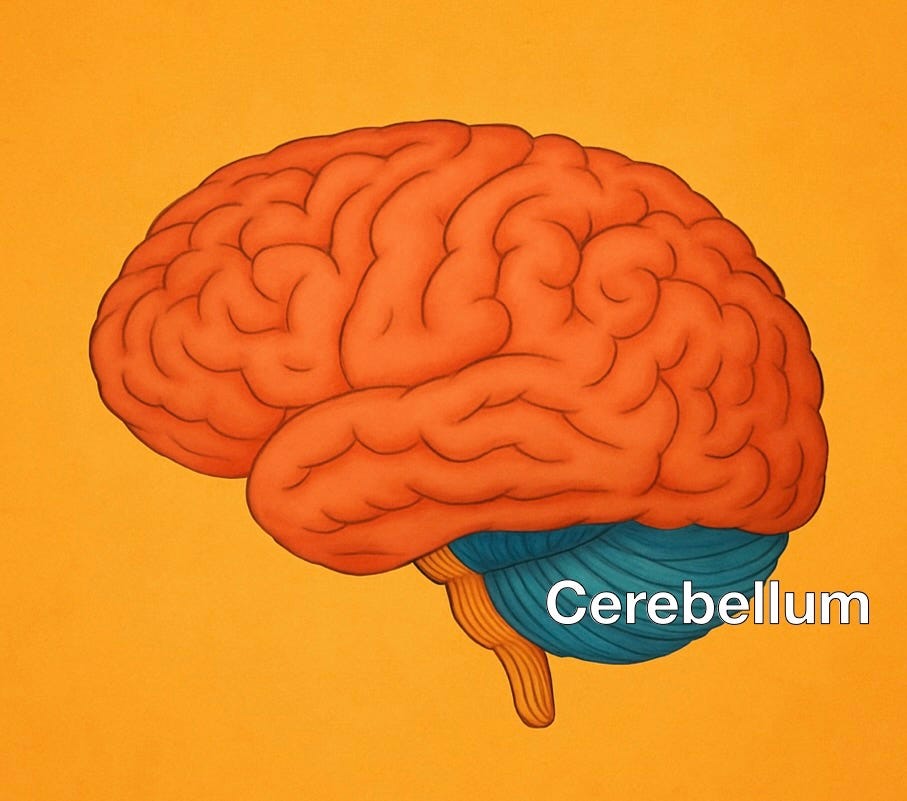

The cerebellum, an ancient structure hundreds of millions of years old, sits tucked at the back and base of the brain. Its job is to fine-tune timing and coordination. If you’re unfamiliar, think of the cerebellum as a real-time quality-control system for movement. It doesn’t decide what you’re going to do — that plan comes from other brain regions. What it does is constantly compare that plan to what’s actually happening in your body and in the environment. Is your foot landing where it should? Is the ground shifting? Are you off balance? It’s the movement auditor.* (Shoutout accountants.)

When there’s a mismatch — you’re off balance, you misjudge timing, or you step in a hole — it makes split‑second corrections to keep your movements smooth and coordinated. This fine‑tuning is also crucial for learning new physical skills, like playing the piano or finding rhythm when dancing with someone, even for those still working through the male‑loneliness epidemic. Metaphorically, if you’ve ever had to bring a camera or microscope “into focus,” that’s what the cerebellum does — but for movement.

Now, if you’ve got a cerebellum that’s new to land — and land is like switching the difficulty setting from “easy” to “hard” in a video game — which cerebellum is more likely to survive and reproduce?

The one that’s better at forecasting and auditing the next half-second, then the next, and the next. Natural selection, over millions of iterations, rewards those small upgrades in prediction. If you keep selecting for the ability to forecast motion and audit more accurately, what might begin to emerge? A nervous system capable of simulating the future with greater agency than before.

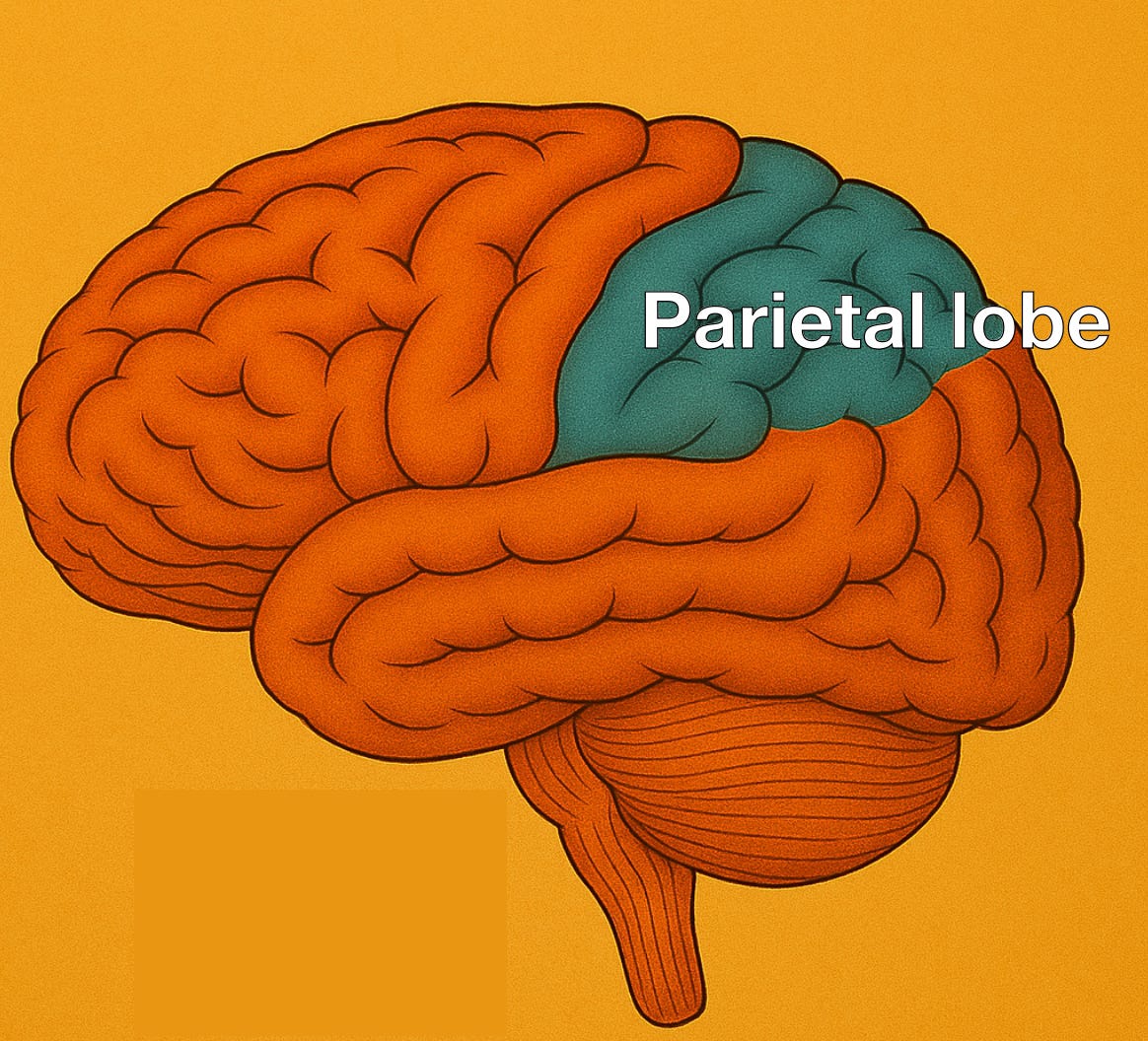

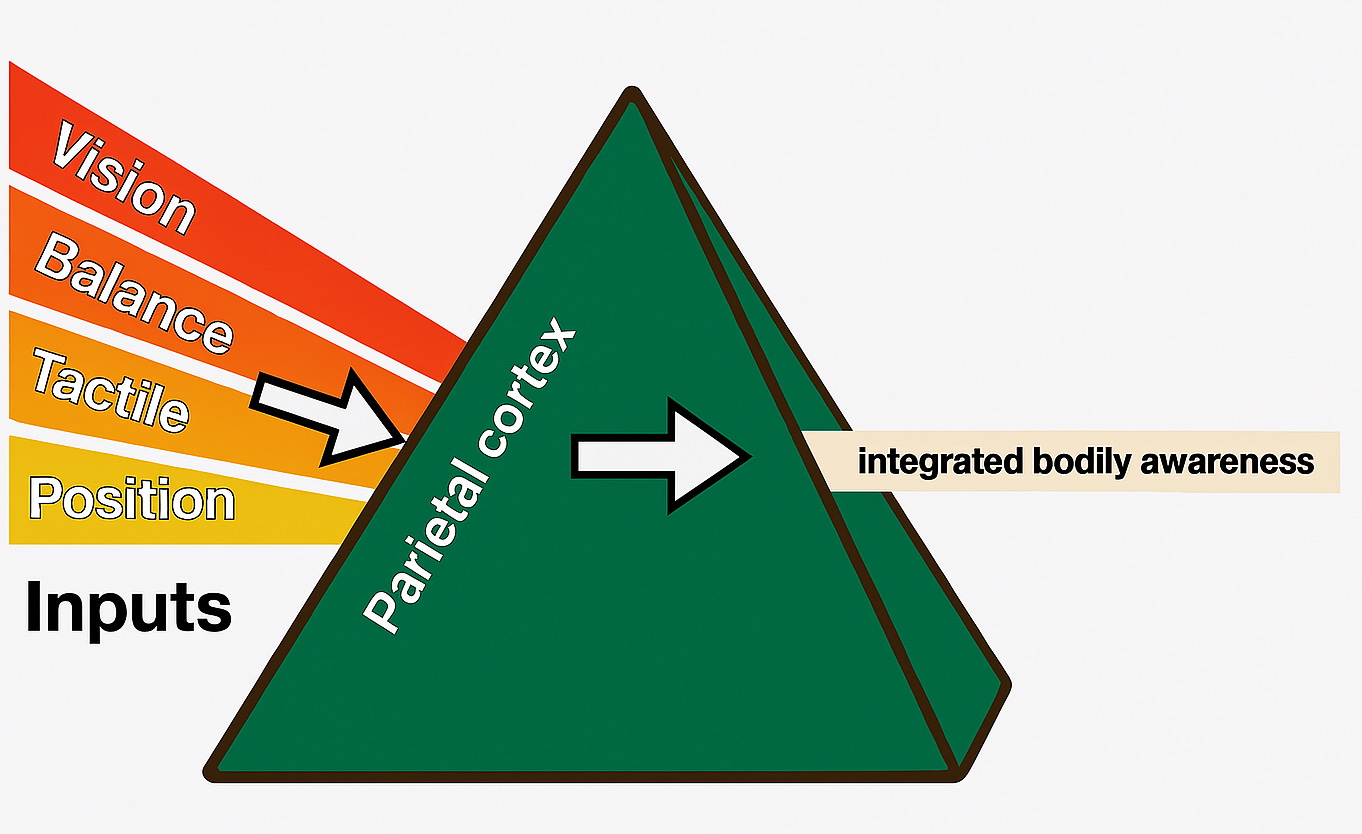

Cerebellum be gone. Much later in evolution, the parietal cortex emerged. For orientation, this sits on the brain’s outer layer — the neocortex — near the top‑back of the head, above the cerebellum. It acts as an integration hub for sensory information, building a constantly updating spatial map of where and how you are relative to the world. This bad boy is how you know where your limbs are without looking, how to reach for moving objects without thinking twice about it, and also why Steve of FIJI College Lore could throw this football over them mountains (judge distances), perhaps the most decent thing Steve was capable of. The parietal cortex fuses vision, balance, tactile feedback, and body position into a single internal experience that answers, What’s around me? Where am I? Am I balanced? Where am I going?

You know how white light can be split into separate colors? The parietal cortex is like that — except instead of splitting the colors (vision, balance, tactile feedback, body position), it fuses them into one cohesive internal experience.

We’ve got two neural tools on the table now.

The cerebellum, our internal motion auditor, constantly checking whether what we’re doing matches what we meant to do.

The parietal cortex, our sensory reverse prism, fusing inputs from vision, balance, and body position into a single internal experience: Where am I? What’s around me? Where am I going?

Running didn’t just demand that these tools function well — it sculpted them. Over millions of years, the need to move fast and fluidly through a highly variable environment placed enormous selective pressure on any neural circuitry that could accurately track position, anticipate terrain, and adapt movement in real time. The better your brain was at modeling reality, the better your odds of surviving to pass it on.

By the time humans arrive — a blip at the end of this 400‑million‑year treadmill — running is already an ancient language etched into muscle, bone, and brain. The parietal cortex’s later expansion added more abstract abilities such as mental rotation (imagining an object’s position relative to you, like what if you were hanging from a tree upside-down, what would the ground look like from that view? What about how would look if you were sitting in dirt, but there was grass to your right?), conceiving extensions of self (tools), and even elements of mathematics, like understanding what is more and what is less — all rooted in its core function of representing space and relationships between things.

The same circuitry that once predicted the next half-second –– keeping us in sync with our own motion, mapping us to the world around us, and stitching all of that into a cohesive experience –– eventually evolved into more abstract abilities: throwing spears, tracking seasons, planning villages, and, at long last, writing poetry. (Thank you, running, for contributing to my ability to have a Substack.) In this sense, running didn’t just help us survive. It assisted in helping us to be able to imagine.

Of course, the full story is more complex. Cognition didn’t arise solely from the act of running, and other Earthly animals with intricate motor systems haven’t put themselves in space or split an atom. Evolution is noisy. It doesn’t operate on single causes alone. Our higher capacities likely emerged from a convergence of pressures. Social, ecological, linguistic, metabolic, etc.

But still, it’s worth considering:

What if our ability to model the world — to mentally time-travel, to simulate what might happen next — began not in language, not in fire, not in culture… but in motion?

What if the brain’s predictive power didn’t begin with a plan, but with a footstep?

In order to run well, you have to predict and adapt, before you take the next step.

And maybe that simple survival need — Where will my foot land? — was enough to spark something extraordinary. Over time, those half-second forecasts may have stacked upward into an architecture capable of simulating not just the next step, but whole futures. Running may not have given us our minds in full, but perhaps it gave us the first glimpse of what a mind could become.

The mental skill of running — prediction and a sense of where an individual was in relation to the world — became the mental skill of living, culminating, at least in part, in humans’ unique ability to consider what was, what is, and what will be, and to, eventually, ask the simple question of what it all means. In many ways, running may have been the match that lit the flame of our higher cognitive abilities.

Why I Run

So, why do I run?

Like I said, it’s c o m p l i c a t e d. Let’s break it down.

For someone like me — an addict, who constantly has to be able to challenge his own thinking ✨ or else ✨ — one weapon I have to wield as effectively as possible to contend with my own ignorance is the ability to adapt and change, even as neuroplasticity naturally declines with age.

Before going further, let’s define neuroplasticity. It’s a term often thrown around in wellness spaces — a space that’s frequently home to things that sound good but aren’t actually understood. So, what does it really mean? Neuroplasticity is the brain’s ability to change and adapt based on experience. Simple enough.

This means the brain can form new connections (synapses — two neurons that communicate across a tiny gap between them where neurotransmitters carry messages), strengthen old ones (long-term potentiation), weaken them (long-term depression), or even shift functions from one area to another (functional reorganization). In short, experience quite literally shapes the brain. Hence, the brain is plastic in a sense, and can be remolded.

For decades, scientists believed we were born with a fixed number of brain cells and that no new ones could be made. No new plastic in the mold, so to speak. You’ve probably heard someone joke, “I’ve only got one brain cell left.”

Me too. Meeeeeeeeee too.

That saying comes straight from the idea of a fixed number of brain cells, that never replenish. But research in the past few decades has overturned it! At least to some extent, the adult brain can, in fact, generate new neurons — a process called neurogenesis, a component of neuroplasticity. And one of the most potent known triggers for this? Running.

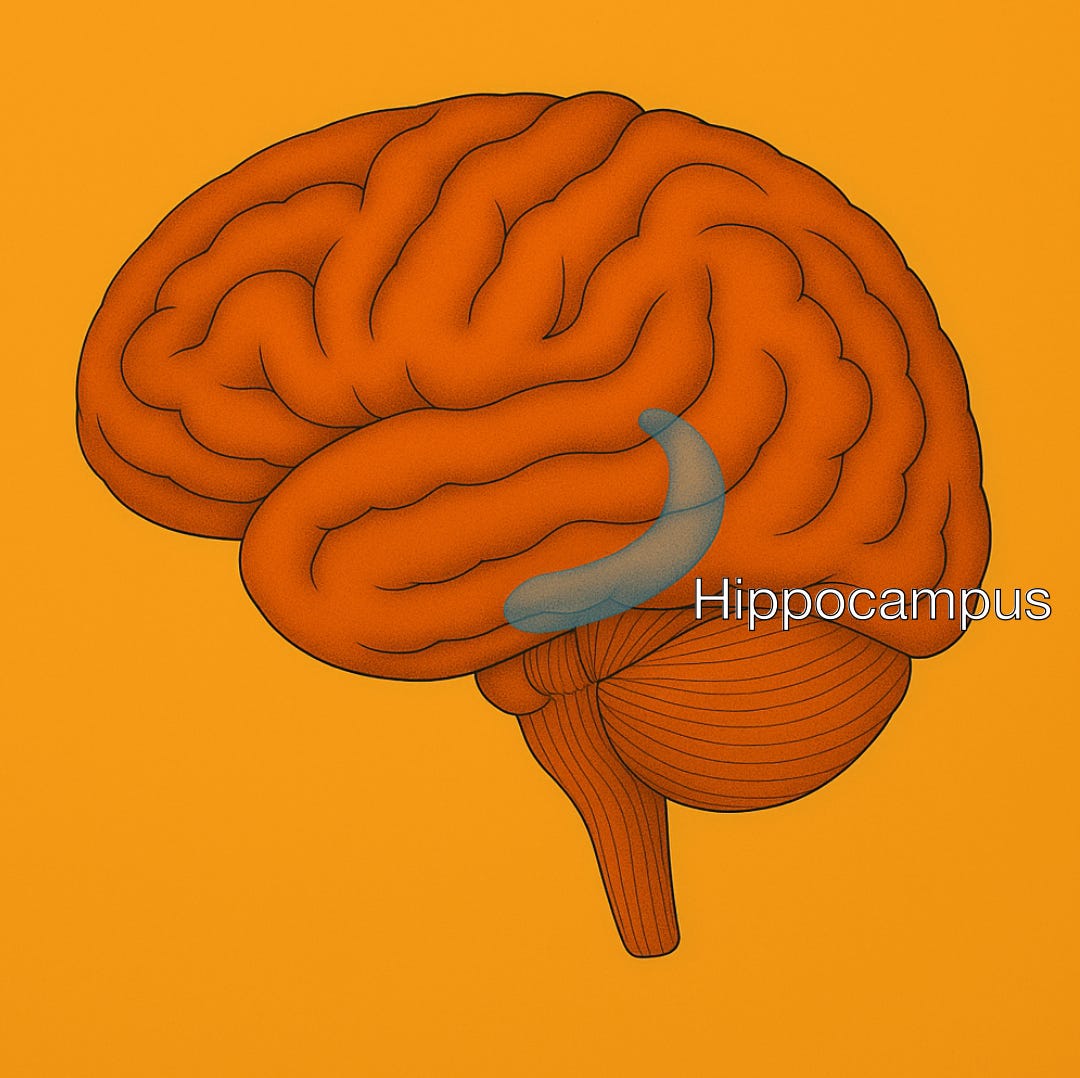

Before going further, let me explain a bit about something called the hippocampus. So many brain structures, it’s a brain party in here. A dendrite disco, so to speak. And just like Nathan in Ex Machina, I’m gonna tear up the fuckin’ dancefloor, dude — check it out.

As an aside, and perhaps the intermission of a much longer piece than anticipated, my article is Kyoko. I’m saying to you, the reader, “Go ahead, dance with her.” Meanwhile, Caleb — my support system — is trying to get my attention with, “Mitchell, you’ve been writing a lot… what about the rest of your life?” And I’m just spinning around under strobe lights like, “What? Check out this routine I’ve got going here, I’ve been working on it”. That, genuinely, might be my favorite movie scene of all-time. Ex-Machina is great.

Okay, back to the article.

The hippocampus is a seahorse-shaped structure buried deep in the temporal lobes — tiny, but mighty. It’s best known for two things: forming new memories and mapping space. Any time you remember where you parked, replay last night’s conversation, or navigate a familiar trail, thank your hippocampus.

Now for the good stuff. One of the most compelling neuroscience findings tied to running is its relationship to neurogenesis — the birth of new neurons — in the hippocampus. Most of what we know about this comes from animal studies, especially those involving mice and rats on running wheels. For example, a 2006 study demonstrated that, in adult rats, running for 30 minutes a day, even for just 7 days, resulted in the birth of new neurons at a significantly greater rate than the rats who didn’t run (van Praag et al., 2006). There are several others studies that have validated this type of finding in rats and other animals, the point is, running reliably facilitates the birth of new neurons, and it is reasonable, if not proven at this point, that this applies to humans as well.***

For me, that means every run is not just training my body — it’s reducing the odds that I’ll get stuck in my old ways of thinking by making me more capable of change. If new neurons are consistently coming online, they’re new puzzle pieces reshaping the picture of who I am, replacing what was believed to be a fixed, slowly decaying puzzle with one that can keep evolving with life as it happens. Current Mitchell becomes less beholden to Past Mitchell, and also more adaptive to what is happening now.

Another reason I run is that it lets me “press on the pain side.” As described in Dopamine Nation, pleasure and pain are closely linked in how we’re wired. What goes up artificially — for me, that used to be drugs — eventually comes down. But the same holds in reverse: when I choose pain on purpose, like running, what goes down reliably comes back up to balance it out. It’s like a see-saw.

That last part might sound strange, but it’s true. If you make yourself high, pain eventually follows. But if you choose to suffer intentionally, you’ll find relief afterward. Hellloooooo cold plunge.

Additionally, I’m someone who lives with PTSD. One treatment that’s gained traction in recent years is EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing). In EMDR, you follow a moving object with your eyes — creating what is known as bilateral stimulation, typically side-to-side — while recalling distressing memories. The theory is that this rhythmic movement helps the brain reprocess fragmented traumatic material, often reducing its emotional charge.

What’s fascinating is that running naturally produces a similar form of bilateral stimulation. Your eyes scan back and forth across your field of vision, and your limbs move rhythmically — left-right, left-right. For me, this rhythm, paired with visual scanning, often helps me see things differently or come to realizations I hadn’t reached before. Not therapy, but therapeutic.

Trauma, by nature, is too much information all at once — too intense, too fast, too overwhelming for the brain to process in real time. So the brain fragments it. Splinters of memory, emotion, and sensation get stored in disconnected pieces. Much of the work of healing from trauma is finding a way to put those pieces back together into something coherent. Something you can understand, get your arms around fully, come to terms with, and move forward from.

Running gives me a consistent space to proceed with that process. My mind loosens, fragments surface, and sometimes, something integrates. A loop closes. It’s a consistent, embodied way of processing what once was unprocessable.

Running is also a kind of continuous pain. All gas, no brakes. But, it’s one I get to choose. There are no timeouts, generally speaking, and that’s part of the point. Life has plenty of ways of handing you suffering you didn’t ask for — and that you can’t readily escape. Everyone has their things, right?

A loved one whose illness you can’t heal, a past that keeps resurfacing, grief from a finished relationship, there are innumerable examples that could be listed — these are types of pain that don’t relent just because you’re tired of them. In that context, running offers a rare kind of authorship. I get to decide what I can continuously tolerate, instead of being forced to endure something regardless of my capacity. There’s a fairness to it — pain with clear terms, chosen and earned. Sign me up.

That’s why this type of pain, on my terms, matters. Running lectures my nervous system, over and over again, to stay present in discomfort without being overwhelmed. It teaches me that I can be uncomfortable without being unsafe. That I can step into discomfort — and step out — whenever I choose. I’m not in a late night, closed-door, one-on-one encounter anymore with a figure of authority, trapped like prey. I’m running. And I. Can. Stop Whenever I. Want to. This type of nervous system regulation is a class I haven’t exactly aced, but one I’m committed to mastering — and maintaining. So I keep showing up and listening to the lecture, day after day.

I also can’t use mood‑altering substances to change how I feel, and running has become a consistent, sustainable way to shift my mood. Outside of Traumaland, I also find myself thinking in new ways, stumbling onto ideas or insights that feel genuinely novel for me internally. I see it as one of the few tools I still have for changing perspective on demand — a much emptier shed, these days. My mental state at the start of a run is often worlds away from where I end up several miles in. It’s like moving down a street in Google Earth and then turning around to look back — it’s the same place, but it looks different depending on your vantage point. Or maybe now that I’ve gone further, I can see new streets entirely — new terrain that wasn’t visible until I started moving.

In summary, I run to make myself as adaptable as possible, to challenge my own ignorance, to process trauma, to reassert my agency in relation to suffering, to teach my nervous system that I’m safe, to change how I feel on demand, and to find new vantage points from which to examine my life and the world around me. Sometimes, I go blank while running. That’s cool too.

To run is to inhabit one of humanity’s oldest evolutionary hand-me-downs. It’s the movement that perhaps bound survival, exploration, and meaning. We ran to hunt, to escape, to migrate, to find water, to find shelter, to find each other. We ran through forests and deserts and across mountains long before we built cities or wrote stories. Running connected us to something beyond ourselves. It was action with purpose. A way of staying alive, but also a way of seeking something more. And in some strange way, perhaps it still is.

Editorial Notes, Expansions, & Addendums

* In more technical terms, the cerebellum compares motor commands (what you intended to do) to sensory feedback (what’s actually happening), and that feedback includes both internal and external sources:

Proprioceptive inputs come from sensors in your muscles, tendons, and joints, telling your brain where your limbs are and how they’re moving — even with your eyes closed. These inputs are how you know how to touch your nose with your eyes closed.

Vestibular inputs, generated in your inner ear, track head movement, tilt, rotation, and balance. These signals help you stay upright and oriented, even while your body is in motion (or recovering from motion). These inputs are how you know your chair is tipping over even with your eyes closed.

Visual inputs come from your eyes and provide real-time environmental context — depth, distance, motion, and objects in space around you. I don’t think we need an explanation here.

Tactile inputs arise from the skin and deeper tissues, offering information about pressure, texture, temperature, and pain — all crucial for reacting to things McDonald’s hot coffee, wet socks, and stepping on a nail.

Auditory inputs offer environmental awareness through sound, which can support timing, rhythm, and spatial orientation. The sound of a car approaching, or how the music is in sync with your stride.

The cerebellum uses all of these signals to constantly audit your motion — correcting errors, smoothing execution, and keeping your movements fluid and adaptive as the world (and your body) shift moment to moment.

** Of course, running isn’t the only way nature has sharpened minds. Consider dolphins and whales. Their intelligence evolved in water — a more forgiving medium to traverse than land. They dealt with currents and echoes, and life in three dimensions rewarded them with echolocation, intricate social bonds, and impressive memory. Or take the octopus, whose neurons spill into its arms like little thinking tentacles. It doesn’t run. It flows, yet still exhibits remarkable intelligence.

Brains, it turns out, can grow for many reasons. On land, the pressure to chase and escape in a less forgiving medium likely forged better movement-prediction machines. In the sea, the pressures were social, sensory, and spatial — a different arms race, but no less demanding in totality. Different environments, different blueprints for success. Running may have helped wire us to imagine trajectories better than anyone else, but there are likely many roads to intelligence.

*** In rats and other animals, researchers can label dividing cells and track new neurons directly. In humans, though, we currently can’t measure neurogenesis that precisely — at least not in living brains.

Why? Because detecting neurogenesis requires invasive methods like staining brain tissue or injecting molecular markers that tag newly formed cells. Doing that to a living person would definitely interfere with their ability to keep running… or doing much of anything else.

Brain imaging techniques like MRI can show changes in volume or activity patterns, but they can’t determine whether a cell is brand new or decades old. So when it comes to humans, we rely on indirect evidence from running studies: larger hippocampal volumes, improved memory and emotional regulation, and increases in growth factors like BDNF and IGF‑1 — molecules that support neuron growth — all of which, in animals, closely track with actual neurogenesis. It’s therefore reasonably inferred that running also promotes the birth of new neurons in the human hippocampus. Personally, I was presented with this finding, in humans, as an established fact during a 2024 neuroscience course at Brown University, so I’m rolling with that here.

Although I’ve done a lot of reading and have had some professional exposure to neuroscience, it’s entirely possible I’m wrong about something. I don’t have all the answers — but hopefully, at the very least, this was thought-provoking and gave you something useful to consider in your own life.

I had AI proofread this piece for grammar and scientific accuracy as far as language used. I do not want to provide “bad info” in my writing. Minor edits were suggested, reviewed by me, and then either incorporated or not. In addition, at times, I went back and forth with AI regarding ideas of mine in relation to my writing as a counsel of sorts. I am still figuring out my exact relationship between writing and the use of AI. If you would like additional information regarding the use of AI here, please reach out to me.

This article has taken me 25+ hours to write, and I thoroughly enjoyed doing so. If you wish to support my work here, please consider subscribing, following, re-stacking, commenting on, and/or sharing my writings. All of these things help in growing an audience that I can do something good with. Some questions that might facilitate discussion:

Why do you run?

If you don’t run, is there something similar you do that you were able to relate to in this piece?

What did you learn from reading this that you’ll take with you?

I am new to writing publicly. Feedback is welcomed and appreciated!

Sources

Aronofsky, D. (Director). (2014). Noah [Motion picture]. Paramount Pictures.

Garland, A. (Director). (2015). Ex Machina [Motion picture]. A24.

Effects of chronic treadmill running on neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus of adult rat, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2006.05.066.

if only your brother felt this way about running

Should I start running do you think?